A few days ago, the BMJ published an Editorial about the Risks of the unregulated market in human breast milk. In a matter of hours, this piece was trending across Facebook and Twitter. Al Jazeera even ran a story featuring this piece. The commodification of human milk is a hot topic, with the Medolac debacle in Detroit, athletes buying breast milk online to enhance their fitness, the New York times coverage of growing profit-driven interests in lactoengineering, and now this.

I read all of these stories with interest, but generally find myself frustrated with the lack of precision used to describe nuances between human milk sharing, milk sales, and milk banking. These distinctions are important. You can’t take the risks of online milk sales and apply them wholesale to milk sharing. Those in public health and medicine need to understand these differences so they are able to engage these issues through policy and clinical practice. The public – and in particular parents as well as potential milk donors – need to understand these differences, so they can make informed decisions.

In 2013, when the highly publicized study of the microbial contamination of human milk purchased online was published in Pediatrics, myself and colleagues put together responses (here and here) to draw attention to the conflation of milk sharing and anonymous milk sales, which was at the heart of sensationalized media coverage of this study. Needless to say, our responses didn’t get much attention. Balanced, evidence-based commentaries of these issues typically do not, precisely because they don’t try to sell the idea that breast milk is intrinsically dangerous.

One of the reasons that people like me are wary of fear-based language, whether as part of a health campaign or a seemingly benign news story, is that such language has been historically been used to deliberately undermine mothers’ confidence in their ability to nourish and nurture their babies through breastfeeding. Fear was used to sell mothers scientifically engineered products that corporations (like Nestle) and doctors claimed could provide babies what a mother’s own milk could not. Fear was used to create general anxiety around early uses of donor human milk. We catch a glimpse of this history every time a mother is told that her milk isn’t nutritious enough, plentiful enough, sterile enough, or that it can be easily replaced by equivocal forms of nutrition, such as infant formulas.

More to the point, opinion pieces like the one published in BMJ get lots of play because they focus on the dangers of human milk, and in the process spread some misinformation.

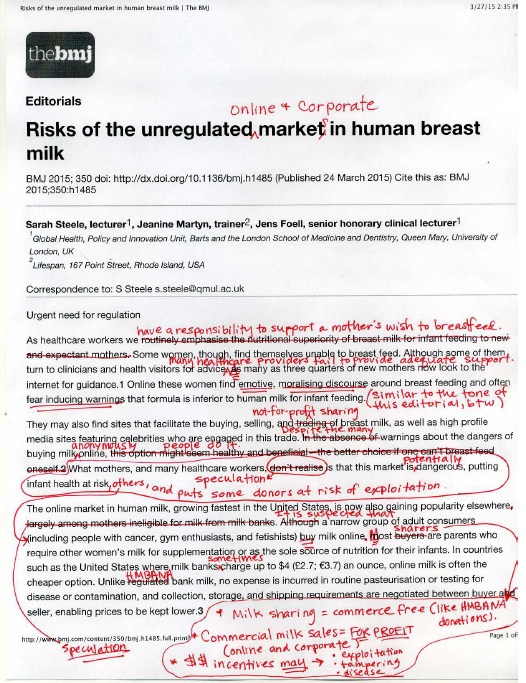

Inspired by the folks at Red Ink, I decided to dust off my red professor pen, to fix a few things:

Commercial milk markets and milk sharing are not the same. These activities may both be facilitated by online social networking, although they also occur offline. Milk sharing typically refers to a commerce-free donation of milk that is privately negotiated between a breast milk donor and a recipient family. Milk sales involve paying a donor for their milk.

Distinguishing between anonymous and informed milk sharing or milk sales is important when considering relative risks. With the Internet, it is totally possible to procure milk from a donor without meeting them, asking any background information, or having any idea about who they are. One study has demonstrated that milk purchased anonymously online and is shipped for delivery carries risk of microbial contamination. We have no idea how often this actually happens, though, as there have been no studies that describe who is engaged in the commercial markets of human milk, online or offline.

Milk sharing is not anonymous. Mothers who share their milk meet and screen recipients to make sure it is going to an infant in need. Parents screen potential donors and meet them, whenever possible, prior to accepting milk for their baby. Milk sharing also often occurs between family members and friends, online and offline. This has been substantiated in four separate studies of milk sharing, including my own [1-4]. There is no standard protocol for milk sharing screening, however, and screening practices reflect a great deal of variability [5].

People who use online social networks to find SHARED donor milk are parents looking for human milk to feed their babies. To be more precise, in our recent published study we found that most of these parents are breastfeeding mothers who have tried to breastfeed, but have experienced disrupted lactation [6]. There are countless ways people come to milk sharing, and just as many types of milk sharing experiences as there are people who share milk. The vast majority of milk sharing donors give milk as a gift without any expectation of compensation. Health care providers have not generally been involved in milk sharing decisions, though that appears to be changing rapidly.

HMBANA milk banks are non-profit organizations, so while there is a price associated with banked milk that is sent to hospitals, these costs cover the expenses associated with screening, testing, pasteurizing, and dispensing milk. The HMBANA does not offer payment for donor milk because of ethical considerations associated with economic barriers to this milk, particularly for critically ill infants. They also rely on unpaid donations as a way to remove financial incentives that may inspire donors to divert milk from their own infant as a way to increase personal profit. HMBANA’s mission is to provide milk to medically fragile preterm babies, regardless of a family’s ability to pay. Still, there are numerous barriers in gaining access to HMBANA donor milk, which is one of many reasons why parents choose other alternatives, even infant formula. By the same token, there are also families who have access to HMBANA milk who choose not to use it.

Parents who are involved in milk sharing generally regard paying for milk with which to feed their baby as an unsafe practice. I would venture to say that the same holds true for most health care providers. The idea that health care providers and parents “do not realize” that these markets are “potentially dangerous” does not resonate with my milk sharing data.

The sale of human milk, and human milk derived products, may involve private negotiations between individuals, but increasingly involve commercial profit-driven interests. Companies who pay donors for their milk often utilize online platforms to facilitate networking and recruitment. Donor milk is then used to develop patented human milk-based medical technologies, which are meant to be sold for profit. The introduction of financial incentives for human milk, both between individuals who meet online and for corporations, carry numerous possible risks and ethical dilemmas: tampering of milk (adding formula, cow’s milk, or water to increase volume of milk); diverting milk from one’s own infant or weaning earlier than planned in order to increase their profit-making potential; potential for exploitation of donors who are vulnerable to predatory recruitment practices; potential exploitation of recipients who are vulnerable to predatory marketing practices; narrowing of already limited access to human milk to babies whose survival may depend on it; and further decreasing access to human milk for all babies in the general population whose short-term and long-term health may benefit from it. These risks extend well-beyond risks of disease, and warrant greater scrutiny. It would also be helpful to know more about women’s engagement with these profit-driven activities, to better ascertain the extent to which these risks of exploitation are realized in everyday life.

It is widely recognized that, in most circumstances where there are no contraindications for a mother breastfeeding her own baby, any form of infant feeding other than mother’s own milk carries risks and benefits that must be taken into consideration. The WHO recognizes this, and recommends that while contextual factors must always be weighed, the milk of a healthy breastfeeding donor is considered just as appropriate as banked donor milk (which is not universally available), and that both of these options are more desirable than infant formula. Probably one of the most thorough and eloquent reviews of the relative risks of various infant feeding methods, however, has been written by Karleen Gribble and Bernice Hausman [7].

The Conversation We Should Be Having….

The first priority in reducing a demand for donor human milk should obviously be providing better support for breastfeeding mothers in the first place. If breastfeeding is treated as a basic human right, then any mother who wishes to breastfeed should be given every resource available to support her in reaching that goal. When this is not possible – and there are many reasons it may not be possible – a baby’s right to human milk should also be protected, as a human right, if this is a parent’s wish. (Some may even argue that this should be the case, even if parents do not consent.)

From where I’m standing, the regulation of anonymous online milk sales is a red herring. I know it’s different in the UK, but here in the U.S. we have race and class-based disparities in infant mortality, preterm birth, and early breastfeeding cessation that, frankly, deserve far greater attention and resources than the regulation of online commercial milk sales. Our efforts and resources should be poured into making breastfeeding an attainable reality for all mothers, not just the privileged few. Critically ill infants need human milk to survive and thrive, but all infants in need should have access to human milk.

If regulation or policy can help to level the playing field so that increased breastfeeding and access to safe donor milk may become a reality, then that’s a conversation worth having. But, I would rather get busy tearing down barriers that stand in the way of mothers breastfeeding their own babies and figuring out ways of delivering breast milk from healthy donors, wherever and whenever it is needed.

References

1. Gribble, K.D., 2014a. “I’m happy to be able to help:” why women donate milk to a peer via internet-based milk sharing networks. Breastfeed. Med. 9, 251–256.

2. Gribble, K.D., 2014b. “A better alternative”: why women use peer-to-peer shared milk. Breastfeed. Rev. 22, 11–21.

3. Thorley, V. 2009. Mother’s experiences of sharing breastfeeding or breastmilk cofeeding in Australia 1978-2008. Breastfeeding Review 2009 17, 1, 9-18.

4. Thorley, V., 2012. Mothers’ experiences of sharing breastfeeding or breastmilk, part 2: the early 21st century. Nurs. Rep. 2, 4–12.

5. Gribble, K.D., 2014c. Perception and management of risk in internet-based peer-topeer milk-sharing. Early Child Dev. Care 184, 84–98.

6. Palmquist, A.E.L., Doehler, K ., 2014. Contextualizing online human milk sharing: structural factors and lactation disparity among middle-income women in the U.S. Social Science & Medicine, 122, 140-147.

7. Gribble, K.D., Hausman, B.L., 2012. Milk sharing and formula feeding: infant feeding risks in comparative perspective? Australas. Med. J. 5, 275–283.

REVISION 30 March, 2015 – Please see the Steele et al’s response to this blog post and other critiques of their Editorial here.

Love this piece. With clarity of words, and dramatic swipe of red pen, all of the elements of the BMJ editorial that were Just So Wrong have been laid bare, and better explained. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Bravo. Such an articulate response. PLEASE submit this as a rapid response to the BMJ.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on bellabirth: informed birth and parenting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great response. Another case of failing to see the wood for the trees.

Can’t help but think of the similarity to the fascination with free birthing in the media: subtext “look at what weirdos are doing now”… when a better response would surely be – “why is this happening?”

…possible answer: “because many women are fundamentally unhappy or don’t have access to the maternity care they want”/ “because women aren’t getting the support they need to breastfeed.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can I please have permission to reblog this on jenhock.com?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, of course!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on jenhock and commented:

Many thanks to anthropologist Aunchalee Palmquist for allowing me to re-blog this response to the BMJ editorial on human milk sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An excellent and much needed response – The nuances of choice of words and omissions of other words has a massive impact especially when many of us are working hard to gain ground for breastfeeding.

LikeLike

You might want to see the authors’ response at http://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.h1485/rapid-responses. Seems they respond to your post directly …

They do point out a number of things about the Journal that seem fair, especially considering the National Health Service in the UK puts so much time, energy and £ into breastfeeding and two of the authors are British, the third seems to have just moved from the UK back to America. It seems a bit harsh to red pen a UK article with North American content especially when they put this in a British journal.Having studied in the UK with one of the researchers, I think you might have been a bit unfair. The BMJ also edit these things heavily before they go out and on our last paper they actually added some errors.

I would also point out that they also can’t control the media around it and I know one of the researchers has been stating everywhere that all feeding options come with some risk. I know Dr Steele and certainly she is a breastfeeding advocate but more worried that people are randomly looking online rather than to breastfeeding support and milk banks.

Maybe next time email the lead researcher before treating them like an undergrad. It comes across harsh and unfair, especially when you change style, content and meaning directly to suit your own agenda ignoring clearly the publication, location and healthcare system in which it was written. Five minutes on an NHS website would have revealed why what you say is totally wrong in the UK…

LikeLike

Andrew the BMJ sent a press release out about the paper and it was picked up in many different countries, including Australia (my first knowledge of it was a call from a journalist asking for comment) and all of the research cited about problems with milk for sale was from (a single- not made clear in the commentary though) US study. I would suggest then that it is very reasonable for those outside of the UK to interpret the paper in the context of their local situation and especially the US. I have appreciated the comments that Sarah Steele has made in the media since the article was published but it is frustrating and entirely predictable that there would be alarmist and unhelpful news articles flow from this paper. That’s the frustrating thing.

LikeLike